Author: Emma McDonough

Activists argue that AI-enhanced license plate readers prioritize police surveillance over transparency, deepening distrust between students and administrators.

The University of Arizona’s decision to install AI-enhanced automated license plate readers without broad student input fuels growing concerns over transparency and trust between students and their administration.

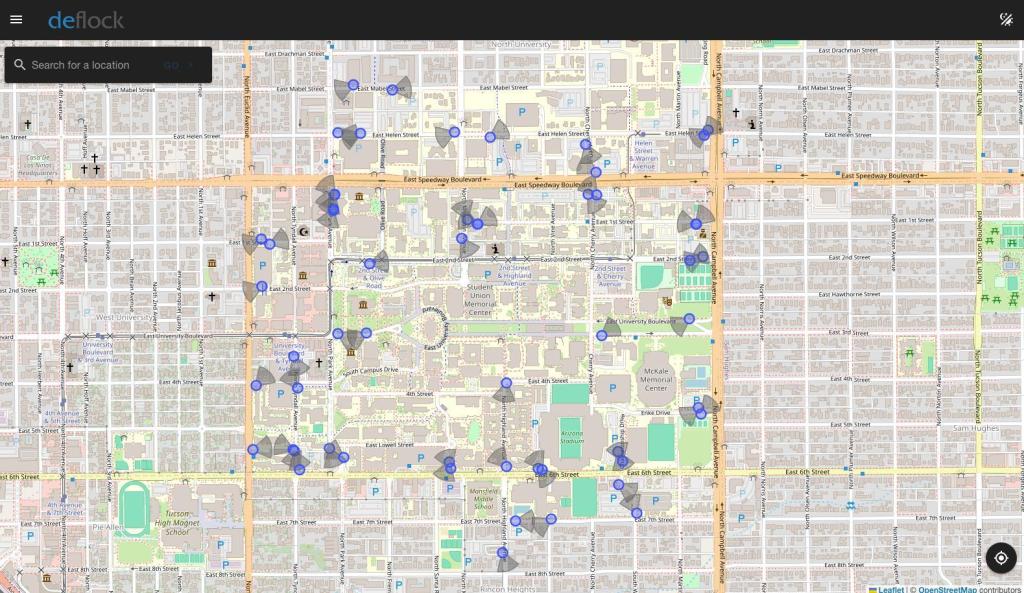

On Aug. 11, Desert Rising Tucson, a non-partisan activist group, began an informational campaign informing the Tucson community of UA’s contract with Flock Safety, a surveillance technology company. According to Desert Rising, the UA installed approximately 54 of Flock Safety’s ALPRs — camera-based systems that capture data — on and near campus.

Flock Safety had multiple controversies with organizations and firms like the American Civil Liberties Union and the Institute of Justice over breaching citizen privacy and other civil liberty abuses.

On Sept. 3, Desert Rising sent the UA administration a cease and desist letter arguing that the university’s continued usage of ALPRs is in violation of the Clery Act, which requires publicly-funded institutions to disclose security measures and other campus monitoring services.

“Such undisclosed surveillance constitutes a failure to include accurate and transparent policy statements regarding campus facility and monitoring,” the cease and desist letter from Desert Rising read.

Desert Rising began a separate campaign, Deflock Tucson, to encourage the university to remove the ALPRs from campus.

As the campaign grew more widespread across campus, student leaders became increasingly frustrated with the university’s lack of transparency in this process.

“I, as a student leader, didn’t even know this was happening,” Eddie Barrón, at-large senator of the Associated Students of the University of Arizona, said.

Barrón argued that this is a direct reflection of the UA administration’s inability to keep students updated about measures that could impact their day-to-day lives. “I think the university administration has a real problem with informing students about what’s happening on campus and what policy and security measures they are implementing,” Barrón said.

Arian Chavez, a student who works with Desert Rising, explained that ALPRs were first introduced during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic as a mode for vaccination enforcement.

Chavez explained that the University of Arizona Police Department is the owner of the data that the ALPRs collect — meaning they have control over how they use the data and who they share it with.

Chavez recognized that UAPD viewed ALPRs as a way to create a safer campus environment. That said, Chavez argued that they aren’t transparent enough on how they collect, share and use data. “UAPD is running themselves in circles over the ‘campus safety’ argument,” Chavez said.

Likewise, Barrón argued that rather than increasing campus safety, this decision will undermine student trust in the UA administration. “I see this as a measure to increase UA’s police state surveillance, not as one to enhance safety,” Barrón said. “If this university was really focused on prioritizing the safety of its students then they would make sure that students are aware of any security measures that involve this amount of surveillance and data on students’ privacy.”

One of the controversial discussions about the Flock Safety ALPRs is the potential for data to be shared with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Chavez explained that UAPD chooses who to give information to. Police departments have Flock Safety transparency portals where they have to disclose where data is sent. That said, Chavez described these portals as notoriously incomplete or misleading, with law enforcement being able to cherry pick information.

Chavez used Boulder, Colorado, as an example. According to Chavez, Boulder police disclosed sharing ALPR information with 90 agencies, but public records later revealed the number was over 6,000 — including information accessed by U.S. Border Control and other ICE-related agencies.

Barrón echoed these concerns for the UA campus, explaining that the university serves such a diverse population of students, some of which may have sensitive immigration statuses.

UAPD Chief of Police Chris Olson ensured that ALPRs were transparent and used solely for campus safety concerns. “Operated under established protocols that comply with privacy laws and regulations, records are deleted after 30 days. Third-party access to the data is prohibited without prior approval from UAPD or a court order,” Olson said in a written statement.

Sarah Young, Ph.D,, is a lecturer at the UA who specializes in surveillance, technology and digitalization that has a more balanced perspective on these concerns.

“I think having an upfront discussion would mitigate some of the fears that people have about surveillance,” Young said.

Young mentioned that other countries’ legislations require more rights for data subjects under surveillance — subjects are assured of what will happen with their data. Since citizens don’t necessarily have those rights in the United States, Young explained that it’s largely up to companies to outline their own ethical guidelines. From Young’s background, most established institutions or police departments are driven by guidelines, policies, core values and mission statements.

“I would assume that [UAPD] established ethical guidelines that set up some checks and balances on surveillance,” Young said. “It’s up to them to be transparent on how they are following those guidelines.” Young expanded that it’s then up to the public to possibly push for different guidelines.

Surveillance, Young stated, generally happens from afar. As a pattern, ALPRs cast a net on everyone in case something goes wrong. This type of surveillance comes out of the theory to grab all of the data possible in case there is a point for it later, Young explained.

Another concern of the ALPRs is that this level of surveillance could discourage students from gathering for activism and using their First Amendment rights to free speech. Barrón argued that the university knows that by increasing surveillance, students will be more fearful of speaking their minds. “I think this is a direct assault on student advocacy,” Barrón said.

Young mentioned that a large sector of surveillance research focuses on how the chilling effects of surveillance could create fear or lessen an individual’s adventure or creativity to speak their minds.

“Surveillance procedures are often meant to curtail what could happen or discipline those for wrongs,” Young said. “I think the license plate readers have the potential to create fear or uncertainty in the student population that could cause them to behave in a way that won’t increase their visibility.”

That said, Young mentioned that there is also a benefit to the chilling effect in that it could prevent those with genuinely bad thoughts from acting out in a violent manner.

Maria Cooperstein, another student activist who works with Desert Rising, mentioned frustrations over the university entering this contract with Flock Safety in the midst of its financial crisis.

Cooperstein discussed the fact that the UA cut student resources such as independent cultural resource centers, laying off several faculty members. Cooperstein argued that funding going into the Flock Safety contract should be turned to things that directly benefit students, such as mental health resources, food accessibility or cheaper housing. “It shows that the administration doesn’t have their priorities set on the students,” Cooperstein said.

The exact amount that the UA spent on ALPRs is unknown. Desert Rising and Deflock Tucson asked for more information, but Chavez said they were only sent data from the Tempe Police Department for reference. For Tempe, the number is in the thousands. Chavez and Cooperstein mentioned that the UA had to spend money on the initial installation, as well as a continued fee for a subscription to Flock Safety’s data collection.

Barrón recognized a listening session between ASUA leaders and Provost Patricia Prelock. “I look forward to bringing up this concern and to shine light that students are frustrated in their university for once again not being transparent,” Barrón said.

Chavez argued that the main concern behind this issue is that students were not consulted throughout the process. “Student voices, as a whole, aren’t heard and they feel more powerless than ever,” Chavez said.

“The police operate under their defined limits for and they probably have the best of intentions from a campus safety standpoint,” Young said.

Young did specify that there’s always unintended consequences from surveillance measures. “As data subjects, when our data is taken or used, we benefit from transparency to ensure it’s not being distorted,” Young said.

For many students, the fight against ALPRs has become less about the cameras themselves and more about demanding a university that values transparency and trust.

Leave a Reply